When it comes to talking about home ownership in this country it quickly divides in to the "have's" and "have not's." According to the OECD fewer than half of low to middle income families are now able to afford to buy a house and some campaigners estimate that, by 2020, families earning the National Living Wage would be unable to afford to buy homes in 98 per cent of the country.

The answer, according to many, is radical deregulation of the planning laws and building on the greenbelt. 8 million new family homes could be built if just 2% of the greenbelt was handed over to developers. To those threatened with the prospect of bulldozers arriving in a field near their home, it will mean urban sprawl and the destruction of large swathes of natural countryside so that builders can make a quick profit.

Economists argue that when the greenbelt was created in 1955 it arbitrarily distorted the market for building land. But the current housing crisis is about moral issues too and in such a polarising debate it's vital that we're able to identify them to get the root of the issue. How do we draw the line between legitimate self-interest and Luddite nimbyism? People talk a lot about inter-generational justice, but do we have an absolute moral duty to provide for the next generation whatever the cost? How do we choose between conflicting moral goods? We all love a beautiful pastoral scene, but does the physical landscape have a moral value beyond how it can be used in the service of mankind? Obviously, having somewhere to live is a fundamental need, but is home ownership a moral good and even a human right?

Anne McElvoy

The Economist (Regular Panellist)

Claire Fox

The Institute of Ideas (Regular Panellist)

George Buskell

Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School (Student Panellist)

Giles Fraser

Church of England priest (Regular Panellist)

Howard Davies

National Association of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (Witness)

Jane Fidge

Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School (Student Panellist)

Maddie Groeger-Wilson

Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School (Student Panellist)

Matthew Taylor

Chief Executive of the RSA (Regular Panellist)

Poppy Cleary

Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School (Student Panellist)

Shiv Malik

Author, "Jilted Generation: How Britain Bankrupted its Youth" (Witness)

Toby Lloyd

Head of housing development, Shelter (Witness)

Tom Fyans

The Campaign to Protect Rural England (Witness)

Michael Buerk

Presenter

“ For my generation, home ownership has been a one-way ticket to prosperity. Some have made more from their houses than from a lifetime of work. For the generation that form our audience here at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, it will likely be an increasingly impossible dream.

House prices have tripled in the last 20 years. If general inflation had increased since 1971 at the same rate as house prices, a chicken would cost £51. There are many reasons for this, but the most important one is the shortage of building land. Small island, crowded at this end, tight building regulations, and the green belt - preserved with the best of intentions to stop urban sprawl, protect our beautiful countryside. But shortage of building land means fewer homes get built. Short supply, increasing demand, higher prices.

70% of the cost of a new home is in the land it stands on. It was less than 25% when I was your age. No wonder there's a growing clamor to unlock the green belt. No wonder there is such vested interest to protect it.

The moral argument is much deeper and more complicated than drawing a line between environmental protection and selfish NIMBYism. Does our physical landscape have a moral value beyond what use it can be put to by humans? What about intergenerational justice? Do we have an absolute moral obligation to provide for the next generation, whatever the consequences? And provide what, by the way? Adequate shelter may be a basic human right, but is home ownership? Arguably, more successful countries, like Switzerland and Germany, prefer to rent. Is home ownership a moral good at all, or merely the symbol of a society whose only moral is materialism? ”

This shows a timeline of who is contributing to the debate when. It also provides and at-a-glance indication of share of discussion to each participant - but remember this is calculated using "utterances" - the communication of single ideas - not time spent speaking. So one participant might express a point in just a few seconds, whilst another might take much longer. Mouseover for more information.

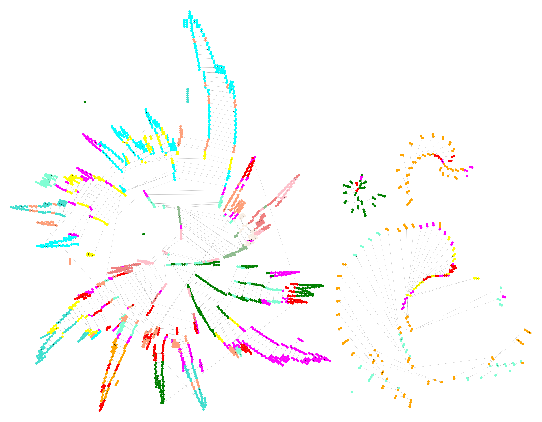

This is the complete map of the debate, showing over 700 utterances, but not showing the links between the to-and-fro of the dialogue and the arguments that were presented (showing everything leads to diagram spaghetti!). To drill down and look at the detail, have a look at the corpus or some of the individual maps created in the analysis tool OVA+. Use the mouse to navigate the map.

But this map only shows the contents of arguments: it doesn't include the detail of the to and fro in the debate. That's a very large map. We can get a 'helicopter-eye view' though, showing how the different participants (shown in different colours) responded to one another.

The debate is analysed above as a large network of interconnected arguments. We can use network graph theory (which has been heavily used in social networks) to calculate various properties of the network as a whole and of parts of the network. One such property is centrality - how close to the 'middle' of the debate a given claim is, based on how much it is talked about, how much the things that are connected to it are talked about and so on. Once we have the most central issues, we can automatically build a word cloud from them.

This shows how much interaction there was between participants. Mouse over to focus on a specific participant. The width of a connection is proportional to the amount of connection. You can see for example that Poppy (purple, far left) spent roughly the same amount of time talking to each of Maddie and Howard, but significantly more to them than to Tom or Jane. Mouseover to focus on one participant.

Not everything that someone says is necessarily picked up and responded to. In fact, typically less than half what is said leads to further discussion. This graphic shows the proportion of a given participant's contributions that lead to further discussion.

Artificial Intelligence has developed a range of mechanisms for analysing networks of arguments in order to determine acceptable arguments - essentially, those that effectively deal with counterarguments. This measure of strength combines an arguments acceptability with that of its counterarguments and its supports in order to identify a rough measure of strength. We pick just a few indicative examples in the graphic. Mouseover and click for more data.

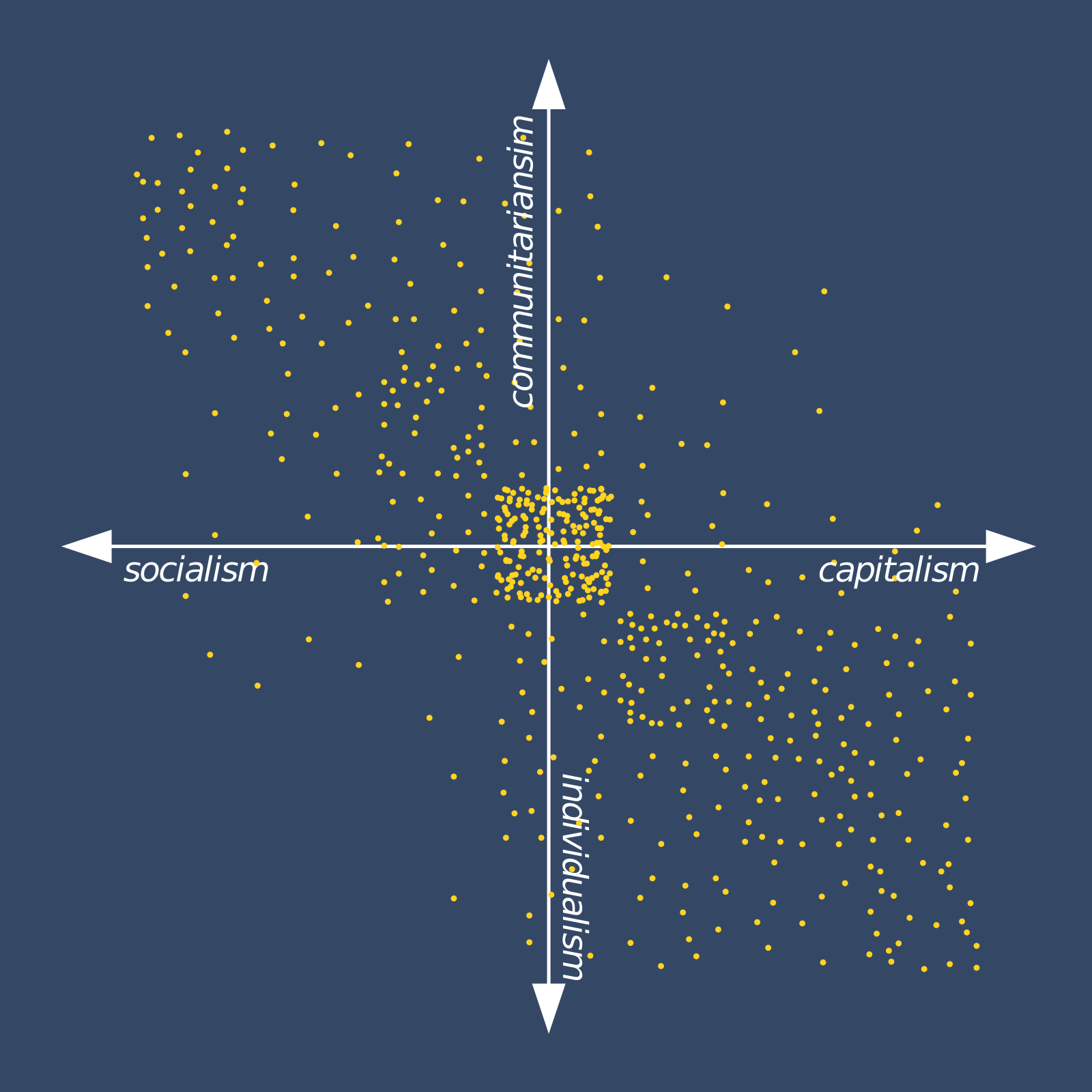

Worldviews capture a set of ideas, thoughts, principles and assumptions that people have when approaching moral, ethical, political and practical issues. We dramatically simplify the set of such "-isms" and plot how many of the arguments fall at different points on a graph mapping two such political dimensions.

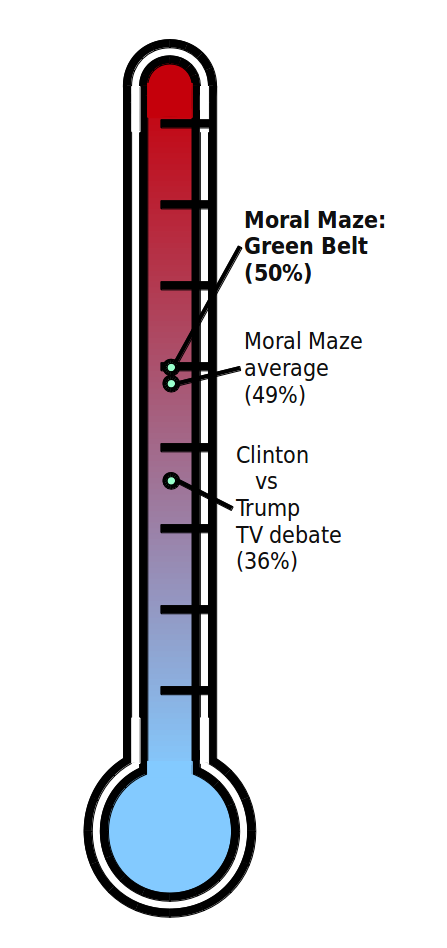

Sometimes arguments are well supported; other times arguments are left unsupported and unquestioned. Sometimes this is because everyone agrees with them; but it may also be a sign that assumptions have been slipped in unchallenged. The degree to which arguments are well supported we call cogency and it can be measured as a percentage. By this measure, this episode of the Moral Maze has very slightly higher cogency than the Moral Maze average (just a fraction of a percentage point), but is substantially higher than other debates such as the first US 2016 televised head-to-head debate between Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump.

Who was on each side of highly divisive issues? Select an issue below to find out!

The green belt per se is not a particularly effective way of protecting nature.

Toby Lloyd

There is nothing wrong with urban sprawl.

Poppy Cleary

The green belt isn't necessarily nature

George Buskell

Human beings are more important than the tree

Poppy Cleary

The issue is when there are genuine human needs, like development and infrastructure, they need to be taken into account first

George Buskell

We don't have a housing market that's delivering affordable homes

Tom Fyans

We've built less than 200 thousand homes a year consistently for the last 10, 20 years

Tom Fyans

We should value more nature than someone having to be on a train for an extra 20 minutes.

Jane Fidge

There are many, many, many other people that want to live in the countryside.

Maddie Groeger-Wilson

Humans are in fact a part of nature

Maddie Groeger-Wilson

The benefits we derive from a healthy functioning environment supports us per se

Howard Davies

It was a very important point to make, that actually we need nature

Jane Fidge

If the green belt is cheap then certainly by opening up the entire area you're gonna create the idea and the ability to create affordable homes in that area

Poppy Cleary

Perhaps we may have to look at the cheapest and easiest solution

George Buskell

Would you have done any better as Michael Buerk? Take on the role of debate chair with debater, an online debate system driven by artificial intelligence.

Argument Analysis and Analytics by ARG-tech